Listed as one of New Zealand’s nine Great Walks the Whanganui River Journey isn’t a walk at all.

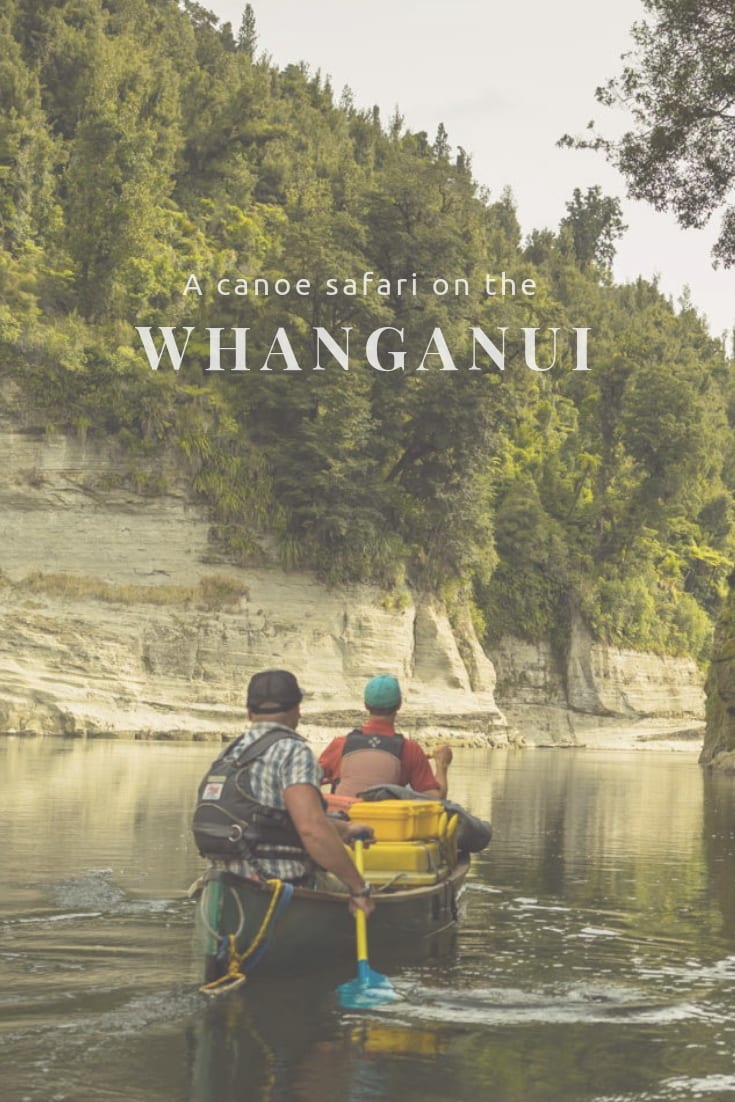

Instead of tramping a well-trodden trail, those who seek to disconnect from the outside world paddle a 157km stretch of water which meanders through some of the most remote parts of New Zealand’s North Island.

‘Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au’ I am the river, the river is me

One of the country’s longest and most scenic waterways, the Whanganui stems from the north-west flank of Mt Tongariro on the island’s volcanic Central Plateau. Flowing gently towards the Tasman Sea, the river is navigable as far north as Tamranui where this unique route begins.

Two days into the recommended itinerary and the river reaches the tiny settlement of Whakahoro. It is here we begin, launching our canoes and easing into a rhythmic paddle as the water carries us slowly towards the coast.

Known to offer the most spectacular views of the entire route, it is this middle section of waterway that leaves me breathless.

I am the river, the river is me.

PADDLING THE WHANGANUI RIVER

From my perch in the front of the canoe my view is unobstructed.

To my left and right vast sandstone walls loom large, blanketed in vibrant green palms and littered with abstract patterns in the rock forged from millennia of lava flow and layered sediment.

Ahead 90km of water to paddle and three days of adventure to enjoy.

At times the only sound is the gentle trickle of water dripping from elevated paddles and occasionally the low pitched murmur of a waterfall is audible over the apparent silence.

As the sun reaches its peak high above, we stop for lunch. From our makeshift picnic bench of river rock we sit and refuel, watching as a waterfall spills over the cliff on the opposite bank tumbling down to the river below.

Back on the river talk turns to the Whanganui’s rich heritage.

In the late 19th century the river was the lifeblood of the region,

says Grant our guide.

Known as the Rhine of the Pacific steamboats traversed north and south ferrying much needed supplies to those early communities living along the river’s edge.

Pioneered by merchant Alexander Hatrick these steam powered paddle boats paved the way for tourism on the Whanganui, with some 12000 visitors arriving each year to experience the beauty of the waterway.

CAMPING AT JOHN COULL HUT

We paddle 37km that first day.

Although the greatest distance we would paddle in one stint, we were assisted somewhat by the flow of the Whanganui, its gentle rapids offering assistance when our muscles began to ache.

Late afternoon the river began to slow and so too did our pace. The rippling water that was once carrying us forward was still, mirror-like reflecting the world above.

Pitching our tents on the banked grassland aside the John Coull Hut (a DOC campsite), we dined on a hearty meal served up by our guide and turned in for the night in anticipation of the day ahead.

THE PARALLEL WORLD OF THE MANGAWAIITI

As we set our canoes in the river early the next morning, a kingfishers darts across the water. The river beckons us to join its gentle ebb and flow, and we set off towards the stretch of water known as the Mangawaiiti.

Although flowing gently south-west, the surface of the river appears still. Vertical rock walls plunge towards the river bed, blanketed in a pattern of green moss and an intriguing pattern which appears to have been etched into the rock.

Worn slanted grooves, what appeared to me as an ornate decoration was in fact a functional structure put in place by the ancient Maori tribesmen to whom the river was a means of transport.

To make the process of paddling upstream a little easier, the Maori would dig their wooden paddles into the rock, propelling their craft forwards against the current.

READ MORE OF MY NEW ZEALAND TRAVEL GUIDES

PADDLING THROUGH A PARALLEL WORLD

Our day is spent in flux between two parallel worlds, above us the walls of the river canyon loom large, and mirrored in the still water below they appear to sink towards an endless blue sky.

We’ve had a few for whom this landscape induces vertigo,

says Grant.

His form mirrored in the river as he talks, I can see how easily the view could play tricks on the mind.

THE BRIDGE TO NOWHERE

On we paddle, towards the Whanganui’s most famous landmark, the abandoned Bridge to Nowhere.

Built in 1935 and now serving as a memorial to the efforts of the men and women who tried to develop the isolated valleys that surround the river, it sits alone amidst a jumble of lush forest.

Leaving our canoes on the Mangapurua Landing beneath the bridge, we scramble up the river bank and along a shaded forest path to the concrete structure.

Constructed of 105 cubic metres of concrete and 15 tonnes of steel, transporting the materials to the building site was a feat of engineering itself let along fabricating the bridge which sits some 40 metres above the water.

THE BRIDGE TO NOWHERE LODGE

Despite the failed efforts to populate the banks of the Whanganui, there are a few sporadic settlements along its shore. Launching our canoes back onto the water, we paddle for a further two hours before reaching the Bridge to Nowhere Lodge.

Set aside the water with unrestricted views of the river, this working farm offers respite to those adventurous enough to explore the Whanganui.

Accessible only by water, the property is blissfully unaware of the outside world, a tiny bubble of paradise removed from the sometimes overwhelming chaos of modern life.

“I have 20 kilometres of the most beautiful road in New Zealand,” owner Joe Adam says, as we gaze out along the river. “It’s the most scenic driveway in the country.”

It is here we spend the night and as the dawn breaks on our third and final day, my body urges me to remain in a cocoon of pillows and duvet.

PADDLING TO PIPIRIKI

For our first few hours on the water the gorge closes in and the river runs narrow and deep. Then the route widens and once again the smooth river rocks are visible beneath the surface.

As the canyon falls away and pastures green appear, a series of rapids are all that lay between us and our route end at the boat ramp in Pipiriki. Splashing through the waves, braced against the thin walls of our canoe, we bounce over the rapids with apparent ease.

One of the first of our fleet of four to tackle this last section of water, we sail straight through, the force of the water spitting us out into the calm embrace of deeper water.

The last canoe through is helmed by John and Phil, and as they enter the rapid it becomes clear that their choice of course has failed them. Skidding sideways into the rapid they begin to take on water, and as if in slow motion their canoe upends itself spilling them and their water tight barrels into the river.

Much splashing and a few choice phrases can be heard as we down paddles to watch, our canoe comes to a halt on the boat ramp as the pair swim to the riverbank. They’d obviously decided to finish this Great Walk on foot.

Want to follow in our footsteps? We joined the team at Canoe Safaris based in Ohakune, and opted for their 3 day guided voyageur excursion.

INSPIRED? PIN THIS POST TO YOUR TRAVEL PINTEREST BOARDS NOW!

✈ ✈ ✈

Have you taken a canoe safari in New Zealand? Share your comments with us below!